I've never tried "hot" yoga (yoga practiced in a room heated to 90-105 degrees at 40% humidity, for 90 minutes), but I have to wonder if "hot" birding might catch on (birding practiced outdoors at temperatures between 90 and 100+ degrees at 70-85% humidity)? I mean, they both involve sweating, potential for passing out if you're not careful, and could lead toward the path of enlightenment if you let them. Birding's a little more passive than yoga, though, with the most taxing position of birding being the constant looking up - which leads, more often than not, to knotted muscles of the trapezius, as opposed to the stretched and relaxed muscles achieved with yoga.

Southeast Ohio, like much of the eastern half of the country, has been very sauna-like over the past month or so, and rolling heat advisories or warnings have been issued off and on throughout that time frame. Folks who work and play outside have been advised to take it easy, to seek shade often, and to drink plenty of fluids. We humans can do a number of things to thermoregulate when it gets hot outside: use fans or air conditioning, wear less clothing, go for a swim or mist ourselves with water, sip cold drinks, eat ice cream, etc. Oh, and we sweat. This is something our bodies do naturally to help us cool off. What are all those birds doing to stay cool? Birds don't sweat, but they do pant. If you see a bird standing around with its beak agape on a hot summer day, it's probably panting. They have other ways to move heat away from their bodies, too. Since there's no feathers on their legs and feet, excess heat can escape from there. They can also hold their wings away from their body and ruffle their feathers, which encourages heat to move away from their skin and body. They can also drink, bathe, and stay in the shade to keep cool. And maybe they even subscribe to one of our human mottos when it gets too hot: "Don't move, unless you have to." Unfortunately, the birds' survival depends on eating pretty frequently throughout the day, and they have to work waaaaay harder for their food than most of us do, so staying idle isn't really to much of an option for them.

Given that it has been so hot lately, it does beg the question of "why bother going outside, especially to WATCH BIRDS?!" Well, if I wasn't surveying for the OBBA II (Ohio Breeding Bird Atlas), I just might not be out there. But then I would be missing the opportunity to see new things and new places, and it would interfere with my continuous desire to study and observe birds. I will admit, however, to calling myself crazy at least once recently while standing out in the baking sun, waiting for a bird to reveal itself. I stayed in one spot for a good 10 minutes trying to ID a flycatcher that was carrying food (Willow Flycatcher), and also trying to get good looks at another bird that was skulking around in some scrubby brush, and who turned out to have a fledgling in tow (Orchard Oriole). Sweat was dripping down my back, the sun was blazing down, and I really questioned my sanity. If I weren't collecting this data for science, there is no way I would have waited these birds out just for an ID.

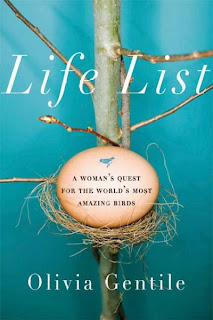

Back in early June, when it was decidedly more comfortable outside and the birds were much more active (establishing and defending territories, building nests, making babies and feeding babies), I was on a roll and I was able to find breeding evidence in spades. I was actively birding most evenings and a lot on the weekends, too. I was riding high on all that I was learning and experiencing for the first time. Then I had to put the brakes on birding for a number of weeks because projects around the house needed to get done, and, for whatever reason, the projects weren't going to finish themselves (that's inanimate objects for you!). Luckily I was able to squeeze in some reading during that time, and of course my reading topic of choice was: birding. I finally read Life List: A Woman's Quest for the Most Amazing Birds.

For those not familiar, it is the story of Phoebe Snetsinger, the person who held the world record (according to American Birding Association criteria) for the most species of birds seen by one person, as of her death in 1999 during a birding expedition in Madagascar (her record has since been broken). While reading Snetsinger's story, I couldn't help but feel a kinship with certain aspects of her passion. She started birding relatively late in life (i.e. it wasn't a hobby she took up as a child), she made it a point to study her birds before she went on any bird-seeking excursion, and she was committed to her hobby. The statements above also apply to my birding experience thus far. Unfortunately, what started out as a hobby for Phoebe eventually turned into an obsession that caused a division between herself and her husband and 4 children. I plan to keep my own birding slow and easy, with bits of excitement here and there. Surveying for OBBA has been one such tidbit of excitement for me.

Participating in OBBA appeals to me on many different levels, and opens a window onto what some of my personality is like. I like keeping lists, keeping track of things and working with numbers, and I especially like watching lists of things that I am keeping track of grow and grow, so this is right up my alley. Even though I am just counting things that are in front of me, it somehow gives me a sense of accomplishment. (Participating in Project Feederwatch in the winter feeds this same sense of accomplishment.) I've even managed to turn it into a game of sorts where I am the sole player and I'm in competition with myself. In this game, I pride myself in the fact that I took the numbers of observed species in "my" 2 OBBA blocks from less than 15 up to figures between 60 and 70 species. It also feels good to have built these numbers up over the course of only a few weeks (with a few incidental records from previous years added in). The flip side of this, however, is that when I work on other blocks, where I have spent much less time and am much less familiar with the territory, I somehow feel bad if I don't come up with what I would consider a "respectable" number during my observation period. I can't give myself a "win," even though I did my best with the time I had. This is what happens with a personality that is always working to best itself.

Surveying for OBBA also feeds my sense of adventure. I enjoy using maps to find my way, and going to new places, and I've now gone to some regions of the state that, while pretty close to home, are not areas that I've had occasion to visit and were thus previously unknown to me. While it's a little frustrating to bird in new places (because I don't know where the "hot spots" are), it doesn't take too long to figure out where the promising strongholds are. Once again, though, there is a flip side to the adventuring element, and it is the benefit of being intimately familiar with an area. My road, my neighborhood, the woods, creeks, streams, wetlands, farms and cemeteries in the two blocks that I "own" have been etched into the map of my mind over the years that I have lived here, and having first-hand knowledge of the available habitats to survey has proved invaluable (and had a direct impact on my ability to observe such large numbers of species).

The current breeding bird atlas is in its sixth and final year, which means I came into the game late, and missed a lot of "good" species as a result because I wasn't able to get out there to enough places during prime time (April-June). I feel bad about this, even though I know I shouldn't. As I mentioned earlier, I did what I could in the time that I had available, and that's all one can ask. Now that we are into August, some birds are already starting their migration south, and breeding is more difficult to confirm. The fecundity of spring, that rush of everyone coming in to set up camp and start a family - that's all gone until next year. Late summer birding is harder, that's for sure: many birds are singing less, they're harder to see, and they aren't as active in the heat. As much as I hate to say it, birding at this time of year is kind of a downer and slightly less rewarding. But there's always SOMETHING to see. Late in July I found Eastern Bluebirds still using next boxes, and I saw several Red-tail Hawks who were requesting food from parents, even though they looked like they were probably old enough to start hunting on their own. I also saw a Tufted Titmouse struggling with a very large caterpillar, and getting a very satisfying meal from it. I keep telling myself that even though it seems like things are slow and languid among the birds right now, it's always worth it to take a good look around. There's bound to be something good going on out there.

2 comments:

I can certainly understand fully what it's like to have what started as a random hobby turn into a time-consuming passion and obsession...but all in positive ways!

Botanizing has allowed me to travel all over the Midwest and into Canada this year, seeing some of the coolest plants with the most incredible people and friends. I have no idea how I'd be able to handle a wife and children and still do what I do so I'm pretty thankful I got hooked relatively young in my single 20's.

Life's too short to not find something that speaks to the heart and soul like nothing else ever could. To find that feeling of perfection and just at peace with everything at that very moment as you watch the prairie grasses sway in the warm July breeze or feel the rays of sun splash your face as you walk under the canopy of an old forest. Life is made for moments like these.

I'm very thankful to have found mine with plants and it's equally exciting and gratifying to see you achieve the same with birds :)

I deal with summer by imagining all the cold days of winter which I will spend standing out in a field watching overwintering raptors. :)

I read Life List too. Phoebe was a piece of work. Utterly focused. Hard core, to the core.

Post a Comment